We know by now that voters are widely scattered and vary in their needs and interests. Plus, political parties increasingly have to appeal to a growing number of swing voters and react to a general declining interest in politics. Searching for new ways of reaching voters, politics is increasingly becoming market-oriented and with this shift, voter targeting has become an essential part of the political campaign strategy. By customising communication to individual groups of voters, a political party can meet their unique demands and interests and help voters decide whom to vote for in the elections. Voter targeting is most effective when using the party’s campaign channels, because information is thus communicated directly, bypassing traditional media. Among the different online communication channels, websites are ideal in giving a clear and transparent picture of what the party stands for. Voters can be informed and persuaded in a more comprehensive and targeted way than by most offline techniques or when appealing to voters via traditional mass media.

The party website

Over the past 15 years, party websites have become more sophisticated and have become an integral part of the overall campaign of Western political parties. Political websites increasingly act as multifunctional hubs connecting the user to different websites and social media of party members, party affiliated organisations or external institutions. Certainly, websites do not necessarily create the opportunity to directly interact with voters such as Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. But websites provide unlimited space to inform citizens about candidates, political issues, the party’s positions, goals and achievements at low costs. Websites can be used to convey an overall impression of the party.

Targeting as a campaign strategy

Targeting is one of the many different strategies that political campaigns rely on to mobilise voters to go to the polls. Targeting is a strategy of appealing to citizens by facilitating resources and providing information addressing their needs, preferences and interests: in other words, information that is actually relevant to their lives. Since the mid-1990s political parties have increasingly focused on narrowcasting strategies — the targeting of specific niche audiences — using direct mail, email, text messaging, web advertising, etc. to microtarget their messages to specific groups of people. According to Principles of Marketing, voter “segmentation is (..) a compromise between mass marketing, which assumes everyone can be treated the same, and the assumption that each person needs a dedicated marketing effort”. The electorate is neither seen as a homogeneous and uniform group nor is each voter seen as a targeted constituent based on his/her actual behaviour. The latter actually needs the help of big data analytics, which parties are only slowly starting to employ. Voter segmentation classifies voters in different groups, whose demands and interests have to be understood. Categorisation is done on the basis of criteria such as age, geography, religion, ethnicity, race, income, education, profession, lifestyle and ideology.

From this rather theoretical perspective the question arises to what degree do parties use their websites to target different voter groups? To identify trends of online voter targeting, we looked at the websites of political parties in the 2008/2009 and 2013 Austrian and German elections.

The study

The study focuses on Austrian and German political party websites of the last two national elections: the 2008 and 2013 Austrian National Elections as well as the 2009 and 2013 German Federal Elections. The Austrian parties - SPÖ (Social Democratic Party of Austria), ÖVP (Austrian’s People Party), the FPÖ (Freedom Party of Austria), Die Grünen (The Greens—The Green Alternative), and BZÖ (Alliance for the Future of Austria) - as well as the German parties - SPD (Social Democratic Party of Germany), CDU (Christian Democratic Union), and CSU (Christian Social Union), FDP (Free Democratic Party), Bündnis 90/Die Grünen (Alliance ’90/The Greens), and Die Linke (The Left) - are part of the analysis.

The analysed parties can be segmented by different classical categorisations: major vs. minor parties, governing vs. opposition parties as well as catch-all parties vs. client parties (Klientelparteien). Approaching parties from the view of catch-all parties and client parties is very interesting when investigating online voter targeting. Classified as catch-all parties are the major parties in Austria, namely SPÖ and ÖVP, and in Germany, namely SPD, CDU, and CSU. Catch-all parties have moved from having strong ideological principles in the parties’ early decades towards addressing a diverse spectrum of potential voters by adjusting policy orientation to the center of the political space. Ideological differences between parties have mainly been reduced due to partisan de-alignment. This development reached its peak in the late 1990s with a movement known as the Third Way, when parties such as the German Social Democratic Party and British New Labour showed an attempt to dominate the center ground. Today, most party manifestos of Austrian and German major parties do not reflect a profound ideological conviction or clear policy goal. Even their policy commitments vary from one election to another election. Following a vote maximisation strategy, catch-all parties concentrate on issues with little resistance (e.g. full employment or education) in order to win the support of heterogeneous voters. They address the views of the median Austrian and German voter who do not adhere to strong ideological principles.

In contrast, client parties have a more consistent idea of what the party stands for and they promote a specific ideology. The Austrian minor parties of the FPÖ, Die Grünen, and BZÖ, as well as the German minor parties of the FDP, Bündnis 90/Die Grünen, and Die Linke, follow a client party strategy. These parties focus on specific topics and very often they enhance the emergence of new issues, such as globalization, immigration and national identity. For example, the Green Parties highlight the importance of an environmental approach to economic issues. Hence, client parties are better to appeal to specific voter groups and have a secure base of support compared to catch-all parties.

All in all, the websites were analyzed for the presence or absence of features such as the party programme, a profile of the top candidate, a calendar with campaign events, donating information, and contact information, as well as to which target groups the element is aimed at.

Trends in voter targeting online

In the 2008/2009 Austrian and German national elections party websites were primarily aimed at the general public. However, the results reveal differences between catch-all parties and client parties as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Comparison of web targeting of Austrian and German catch-all and client parties

|

Website features addressing |

General Public |

Specific Target Groups |

General Public |

Specific Target Groups |

|

|

2008/2009 |

2013 |

||

|

Identifications of Target Groups by Austrian Catch-All Parties |

36% |

64% |

60% |

40% |

|

Identifications of Target Groups by Austrian Client Parties |

36% |

52% |

56% |

44% |

|

Identifications of Target Groups by German Catch-All Parties |

36% |

64% |

54% |

46% |

|

Identifications of Target Groups by German Client Parties |

53% |

47% |

60% |

40% |

A different pattern is revealed for the 2013 campaigns. The comparison between catch-all and client parties reveals a similar targeting pattern with a focus on the general public across countries. The cross-national analysis clearly shows that differences between catch-all and client parties have been reduced.

But what about the specific target groups? At which target groups do parties aim their online communication?

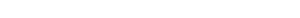

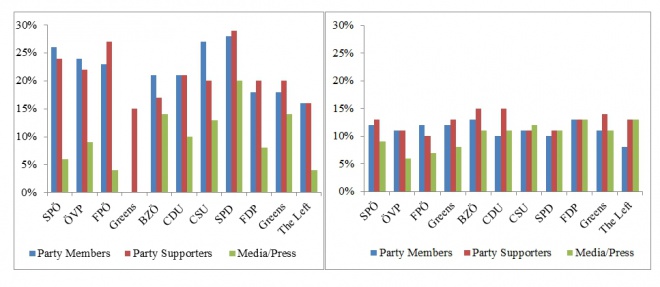

After addressing the general public, parties clearly prioritise two groups: party members and party supporters. However, in the 2013 election campaigns the two key specific target groups, party members and party supporters, were addressed to a far lesser extent than in 2008/2009.

Figure 1. Comparison of targeting at party members, party supporters and mass media

2008 2013

The targeting of the other niche audiences is a neglected strategy by the parties. Political online communication is not tailored to the requirements of specific age or identity groups as shown in Table 2. In 2008, when Austria had just lowered the voting age for all elections to 16, parties offered a very few information on their websites for young(er) people, i.e. first-time voters. But Austrian parties hardly continued to address this internet-savvy group of voters in the next elections.

Table 2. Web targeting of specific (niche) audiences

|

|

Young Voters |

Seniors |

Women |

Minorities |

Gays |

|||||

|

|

2008/09 |

2013 |

2008/09 |

2013 |

2008/09 |

2013 |

2008/09 |

2013 |

2008/09 |

2013 |

|

Austria |

4% |

2% |

3% |

2% |

2% |

2% |

1% |

1% |

1% |

0% |

|

Germany |

0% |

2% |

0% |

2% |

0% |

1% |

0% |

2% |

0% |

1% |

Is targeting an effective online campaign strategy?

Trends in voter targeting online can be summarized as followed: a) information and services on political parties’ websites increasingly focus on addressing the general public, and b) differences between parties were reduced between campaigns.

This finding seems to contradict the debate about politics increasingly becoming market-oriented, customising communications toward each individual voter. From this viewpoint, parties’ online targeting strategies have not become more sophisticated. The question is whether this trend is due to the constant decline in voter turnout and an increase in the volatility of party preference. Moreover, with the approach of new parties such as the AfD in Germany or the NEOS in Austria, voters have more choices. So all parties try to appeal to as many of the few people who still cast their vote. Parties are running a catch’em all-strategy.

Nevertheless, the rise of swing voters shows that voters need orientation and political parties should not exacerbate the decreasing levels of voter participation. Voter responsiveness — providing information that responds to voters’ expectations and interests — should increasingly be a strategic concern. Right-wing populist parties such as the FPÖ in Austria clearly show that parties can gain voter support when a party spreads consistent ideas and specific positions and clearly addresses its potential voters. Political parties should develop a map of party’s relevant groups of voters and their basic needs and interest and accordingly offer more targeted communications. Identifying and segmenting online stakeholders is, in fact, fundamental for strategically managing organisation’s decisions.

Image: Thinkstock

|

References: Blaemire, Robert. (2003). Targeting: Getting the Most Out of What You Have. In Winning Elections. Political Campaign Management, Strategy & Tactics, ed. Ronald A. Faucheux, 224–228. New York: M. Evans and Company. Hillygus, Sunshine D., and Todd G. Shields. (2008). The Persuadable Voter. Wedge Issues in Presidential Campaigns. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Howard, Philip N. (2006). New Media Campaigns and the Managed Citizen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Kotler, Philip, Veronica Wong, John Saunders, and Gary Armstrong. (2005): Principles of Marketing. Fourth European Edition. Essex: Prentice Hall. Lee-Marshment, Jennifer. (2010). Global Political Marketing. In Global Political Marketing, ed. Jennifer Lees-Marshment, Jesper Strömbäck and Chris Rudd, 1–15). London and New York: Routledge.

|